MEXICO CITY. – In early April, a waiting-line formed in Havana that extended for close to 20 blocks, where more than 1,000 people stood to have their names written on a list. This would allow them to make purchases in the future at a network that sells food products and other basic items in national currency: in Cuban pesos. People waiting on the line said they didn’t know what would be sold, or when, or if there would be enough for everyone. What is clear is that everything they were looking for was really located in one place: Supermarket23.

This webpage is the closest thing in Cuba to Amazon. It’s an online store where it is possible to find more than 1,000 different products, from meats and ice cream to any personal hygiene and cleaning products and medicines. Precisely what there is a shortage of in the country.

All you need is a couple of clicks and entering the number of a credit or debit Visa or Mastercard card associated with an account in some foreign currency, to have the items purchased delivered later in Cuba. Yes, at Supermarket23 one can find everything that is lacking in state stores, but not everyone is allowed to shop here.

In Cuba, very few people are paid their salaries in foreign currency. And domestic banks do not issue Visa or Mastercard cards.

In other words, the world of abundance in Cuba’s Amazon equivalent is only available to those who have relatives or friends abroad who are willing to pay for the products they need.

Supermarket23 is not the only online sales webpage in Cuba. In the last four years, these online stores, designed so that Cubans abroad can send their relatives food and other essential products, have proliferated, and using them has become commonplace for the growing Cuban émigré community.

However, Supermarket23 excels among its competitors. First, because of its outreach: it delivers its products practically to every Cuban municipality. Second, because it offers variety: one can find almost anything on its web. And third, because contrary to other businesses of this type that seem to be promoted by foreign businessmen, all the evidence leads us to assert that Supermarket23 is an initiative promoted by a Cuban state company: Alcona.

This entity is part of the state entrepreneurial group Flora y Fauna, a dependence of the Ministry of Agriculture. It is run by one of the last living comandante of the Revolution: Guillermo García Frías, aka comandante avestruz, or “Commander Ostrich”.

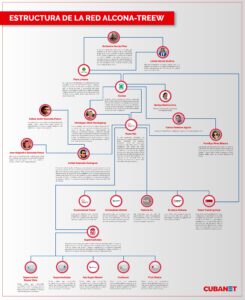

In spite of the fact that it has been presented as a foreign company without links to the regime, in reality, Supermarket23 has behind it a network of businesses in different countries created by individuals who worked for Alcona or for a company linked to Alcona in order to conduct trade abroad, as this investigation was able to corroborate.

In our research, we found at least another 11 webpages created by Alcona-linked companies, or companies that are identical in products, prices and design to Supermarket23.

In this fashion, the enterprise headed by comandante García Frías has joined the group of most profitable businesses to emerge in Cuba in the context of the present economic crisis. At Supermarket23, it is possible to sell the most basic products at outrageous prices. A 50-ounce container of syrup that could be purchased for US$ 2 in physical state stores, costs four times as much at Supermarket23. Cuban émigrés who have the purchasing power to buy these products will do so, even at those high prices, because it is their only option if they want to provide for their families.

The rise of this web is not coincidental. Although the government has not stated it openly, some state communications media have introduced the so-called “border purchasing” as a priority during the present economic reform period, the so-called Ordering.

This strategy implies that state companies must sell in hard currency as much as they can. Theoretically, the purpose of this should be to promote exports to other countries. However, for companies like Alcona, the new strategy means that now it is “exporting” food products that really never leave the country.

From Alcona to Supermarket23

Flora y Fauna is an entrepreneurial group whose main purpose is to manage some 80 protected areas in the country. It also attempts to exploit any business that is related to Nature as long as it generates profits in order to, in theory, finance environmental conservation.

Some of its affiliates are involved in ecotourism in places like Parque Natural “El Bagá” or Ciénaga de Zapata (the Zapata swamps in the southern coast of Matanzas province).

Others are cattle-industry companies that produce beef.

The activity that this group promotes the most is the exporting of charcoal – obtained from the cutting down marabú bushes, an invasive species- as well as ornamental fish, thoroughbred horses, and fighting cocks. Flora y Fauna is the only entity in Cuba that is authorized to export living animals.

The sale of animals and charcoal is made through one of the best-known companies in the group: Alcona. This company takes the name of the farm where animals are raised and cock fights are organized, a legal activity that has been criticized by animal-rights activists in the country.

From its founding in 1976, Flora y Fauna has been headed by Revolution comandante Guillermo García Frías, an old farmer who is 94 years old today, who fought alongside Fidel Castro in the Sierra Maestra mountains.

García Frías was at one time Minister of Transportation, and was part of Cuba’s high military command. However, in the last decades, he has been known mainly for heading Flora y Fauna and for having turned the group into his personal feudal estate.

The company reflects his preferences –breeding horses and cock fighting- and is managed like a family business. Second in command is his daughter, Loreta García Sardina. Loreta’s son, Jorge Alejandro de Cárdenas García, also works for the group. In spite of his youth, Cárdenas García also is vice president of the Equestrian Federation, an entity that his grandfather manages as well.

In the last ten years, Alcona used a company called Treew to export its products. Treew is presented as a foreign company with offices in Canada, Panama, Spain and the United Kingdom.

Treew has organized companies in all those countries, and one of its main officers is a Canadian citizen whose name is Christhopher Mark Hemingway. Hemingway has been doing business with Cuba for twenty years, purchasing charcoal and thoroughbred horses (Alcona areas), in addition to trading food products. Another Canadian individual, John Hyeon Kim, is listed as officer of Treew on its registration.

However, as happens with other companies that trade in Cuban products, it isn’t clear to what extent Treew is a real private entity or an extension of Alcona. It’s common for Cuban state companies to resort to offshore operations, or to use front men in order to go unnoticed and often to avoid United States sanctions.

Treew is not engaged in any other known activity except the trading in Cuban products. All workers that its supermarket has registered in Linkedin are Cuban, some of them well connected to the government elite, like Luis Mazorra, whose father was diplomat Gustavo Mazorra, president of the Cuban Institute of Friendship with the People (ICAP, by its Spanish acronym). Luis Mazorra has promoted the company on his social networks and works for Treew as a manager. In addition, two of Treew’s principal officers have tight links with Alcona.

One of them is Yureibys Pérez Blanco, the wife of Carlos Quintero Agullo, who has stated on his social networks that he was financial director of Alcona. This was confirmed, on condition of anonymity because he/she still lives in Cuba, by a source that knows the operations of the company well. Our source described him as being very close to Loreta García Sardina, comandante García Frías’ daughter.

Another one is Aníbal Quevedo Rodríguez, who also worked at Alcona in the 1990s, according to the same source, who described Quevedo as “a front man of the regime.”

Both Quevedo and Pérez Blanco, hold legal residence in the United States and in recent years represented several of Treew’s companies in Spain, Panama and the United Kingdom for exporting Alcona’s charcoal.

They also engaged in the management of companies whose aim was to start electronic commerce pages. One of them is Supermarket23.

Quevedo is portrayed as an online sales expert, and a pioneer of this branch in the country. In 1995, he managed the state company that established the first ever Cuban webpage: cubaweb.cu. Since then, he has been engaged in various enterprises with the sole purpose of earning hard currency for the regime, like Únicos Habanos, a cigar-selling online sales page.

Quevedo is also a prosperous man, who has managed to launch his private businesses. His son, Juan Alejandro Quevedo Ponce, who holds positions as well in a Treew affiliate in Spain, has the 25MN Restaurant in Havana’s El Vedado, registered in his name, as well as another private business on the same block – Nana Café- which is operated by Quevedo’s wife, Iliana Ponce.

For years, Treew and its officers, as evidenced on the company webpage, seemed to concentrate on Alcona’s traditional activities, especially the export of charcoal and supplying beef to the hotel sector.

At first, online sales were a low-profile activity. However, starting in 2017, everything changed. As the country sank in an economic crisis that lasts until today, and shortages of consumer goods increased, online commerce experienced a rise without precedent.

Treew officers began to create companies dedicated to this activity, as the trading records of several countries show. They multiplied stores and products for sale, and created a variety of webpages aimed at the different Cuban communities abroad.

Supermarket23 was the star of this strategy. After being created first in Canada, the company launched an affiliate in the state of Florida, in the United States, which Quevedo himself launched. His other son, Aníbal Javier, appears as its director, and slowly he began to attract more consumers.

However, along with this webpage, other websites emerged. Some were directly created by Treew officers: Supermarket Treew, En Plaza Habana, Almendares Market, Treew Trending (which only sells charcoal, no food products) and Habana Rx. In other cases, if we could not establish a direct link to Treew or Alcona, their websites are identical to Supermarket23: the same design, the same prices and presentation texts. That’s the case with online stores such as Supermarket50, Isla Super Market, Cooltuset, Supermarket Buena Vista and First Choice, all of which were created primarily in Spain.

In total, for this investigative report, 11 online stores associated to the Alcona-Treew network were identified.

In addition to commercializing food products, this organization also created a medicines store: Habana Rx. This business was incorporated in Florida in 2021 by Quevedo and Yureibys Pérez. On this website, one can obtain everything from pregnancy tests to pharmaceuticals that require a doctor’s prescription, like antibiotics, although the supply fluctuates.

Meanwhile, the country was sinking into the worst economic crisis since the end of the Special Period. The greater the shortages, the greater the attraction for these webpages and their ability to supply.

The products that are lacking in Cuba are found online

The link between Alcona and Supermarket23 are obvious. The site identifies who its suppliers are, and all you need to do is navigate the page to corroborate that several of the food products that are being sold come from Alcona or other affiliates of Flora y Fauna.

A 4-pound package of Alcona beef can be found for US$ 33. A package of top round beef from Empresa Pecuaria Genética Turiguanó, associated to Flora y Fauna, can be purchased for US$ 28.

When you navigate the Supermarket23 webpage, it is also evident that it has become a sales platform for other state companies, and even for some private businesses.

On the online store, one can find products from Palco, owned by the military group GAESA, and from paladares –home-based restaurants- like Ola Dinners, Tamys Cake and Nana Café, the business run by Quevedo’s wife.

However, a great part of the products for sale come from business groups that belong to the Ministries of Agriculture or Food.

In fact, to navigate Supermarket23 is like time travelling in that domestic brands that once could be found in local currency at the Ideales markets or at convertible-currency stores, are available here again.

We are talking about Conchita sauces and mayonnaise, Taoro or Tuaba marmalades and tomato sauce, Sanitec toilet paper, Ciego de Montero sodas, powdered milk, Bravo beef products and Guanaroca ice cream.

All these products that, up to two years ago, were sold in physical shops that accepted Cuban pesos, are difficult to find anywhere, much less in national currency. However, they are readily available at Supermarket23.

Residents in Cumanayagua, Cienfuegos, for instance, were used to buying Guanaroca ice cream directly from the municipal factory, the state Empresa de Productos Lácteos Escambray. Now, they can only get it if someone from abroad pre-pays for it with a Visa or Mastercard.

This ice cream is available at Supermarket23 in 1-gallon containers for US$ 13 or 14, one fourth of the average monthly salary in 2020.

What has Alcona said?

Alcona authorities have yet to mention their relationship with Supermarket23, but neither are they hiding that now they sell some of their products online.

In an interview with Cubavisión Internacional, Alcona director, Berkys Medina Urra, explained that since the start of the pandemic they have resorted to this strategy.

She did not reveal what online platform they are using, nor was she asked. Medina Urra only explained that the idea had emerged thanks to “the opportunity presented to us by four foreign companies that are our clients” and that in 2020, Alcona had made US$ 600,000 in online sales.

She added that, in addition to selling products, Alcona also stored goods and delivered them to clients’ homes.

This would explain how Supermarket23 delivers its products so quickly in Cuba without being registered as a foreign company: Alcona is in charge.

Photographs circulate on social media that show how the Cuban Amazon utilizes white vans with their logo on them for delivering goods. The vans have state-vehicle license plates.

Other state companies have openly admitted their relationship with Supermarket23. In a press note in the official paper “5 de septiembre”, Empresa de Acopio Cienfuegos, which distributes agricultural products grown in Cienfuegos province, explained that part of their products is sold on Supermarket23. Suchel Proquimia, manufacturer of cleaning and personal hygiene products, also admits to having a commercial relationship with this website.

However, no state entity has explained who is behind Supermarket23, or how, in a country where the state controls every aspect of economic activity, this company manages to sell online items that are lacking in physical stores.

Empresa de Acopio Cienfuegos presented Supermarket23 simply as a “Canadian company.” This promotes the notion that the state has no relationship with the website and that, in addition, state companies are exporting their production. The reality is quite another story.

Supermarket23, through its officers, does have tight links to the government sector that surrounds Alcona. And no: food products never leave the country, although its earnings are in hard currency, a practice promoted by the Cuban state.

Border purchasing

That such confusion has been fostered is not accidental. It allows the government to distance itself from something that is unpopular, that promotes inequality between those who received money from abroad and those who don’t, and it incentivizes migration.

In the television interview that Alcona director provided, she was careful to emphasize that the food products it sells online are the ones it used to market to the hotel industry. According to its version of the facts, Alcona was not depriving the population of products it could access before.

In a subtle way and without being questioned by anyone, Medina Urra was responding to criticism already rampant in the country. According to her, in spite of the evidence, online sales does not curtail the availability of food items for people with no relatives abroad.

However, the rise of online sales coincides with a shortage crisis which is evident to Cubans, comparable to the 1990s.

Official data serves to corroborate it. The volume of agricultural and food products available for purchase in retail shops dropped 30% between 2018 and 2020 alone, according to the National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI, by its Spanish acronym).

It’s precisely this drop in the availability of basic products that makes websites like Supermarket23 more attractive. If food products were available at physical shops, or virtually at prices more in tune with salaries that are paid in national currency, why would someone have to resort to relatives who live in the U.S. to send them two pounds of beef sold by Alcona at three times the normal price?

In addition, the proliferation of webpages similar to Supermarket23 suggests that the model shall multiply in the future.

For example, Katapult and Mall Habana, are similar businesses that are managed by entrepreneurs close to the regime. In the first instance, we are referring to Cuban American Hugo Cancio; the second webpage is owned by Spanish investor José Carlos de Santiago.

To wit: the creation of Supermarket23 is not just the result of an Alcona idea.

Online sales aimed at Cuban émigrés is part of a strategy called “border purchasing”; it has become one of the pillars of government companies to garnish hard currency.

With a decline in tourism as well as in the main sources of U.S. dollars for the country, such as medical missions and remittances –which has been restricted from the United States- “border purchasing” has become one of the new paradigms.

More so now, during a period of reform –the so-called Ordering- when state agencies are no longer being subsidized and are forced to secure their own hard currency by exporting what they can.

When explaining the nature of “border purchasing”, official sources have insisted that it is mainly about selling products for U.S. dollars or euros to foreign companies located in the Mariel Special Development Zone, a free zone located at the island’s main port.

However, officials have opted to not talk about the fact that another model of “border purchasing” consists of obtaining hard currency from the population itself, selling directly articles of basic need that Cubans cannot find elsewhere.

In this manner, companies that belong to civil ministries, like Alcona, are being incentivized to replicate the practices of the unpopular Armed Forces business group GAESA. During the July 11, 2021 protests, several GAESA stores were looted by protesters.

GAESA controls the majority of physical stores in the country, where a system has been set up so that paying for merchandise can only be done with cards linked to foreign currency accounts. These are the convertible-currency only stores. Only Cubans who receive remittances from abroad or can get their hands on hard currency in the informal market, can access these stores.

Since other business groups do not have physical-store networks, they are relying on the web to do business. But, contrary to GAESA who sells mainly articles it imports, these businesses are commercializing the very same goods they produce or buy from other state producers, goods that could be purchased with Cuban pesos before. This has increased discontent in the population.

That the government is selling domestic products in hard currency through the web is not new. The government has been operating for years a website called Tu Envío; its objective is to secure hard currency from Cuban émigrés. The Alcona farm was already selling its products through this website.

However, not until now had online trading reached the magnitude it has at present, and neither had it been handled with such secrecy.

Tu Envío has been openly operated by state companies. Supermarket23, however, has operated amidst government silence.

This has incentivized the company to do things that have angered the population, like selling four pounds of chicken breast for as much as US$ 40. It has also allowed the government to claim that it is against “abusive” prices.

In mid-May, Cuban Prime Minister, Manuel Marrero, one of the promoters of the so-called Ordering reforms, spoke in defense of consumers at an extraordinary meeting of the People’s Power National Assembly. Although he didn’t mention any company in particular, Marrero enunciated criticism, as follows: “We have to help our people, it’s not fair to charge those abusive prices, we don’t understand anyone who can charge up to ten times what goods are worth, we cannot allow that some become rich at the expense of the people.”

*** Note: CubaNet consulted SuperMarket23 and Alcona for this investigative report. Only SuperMArket23 accepted to answer CubaNet’s questions, but until the time of publication, it has not answered our questionnaire.

Recibe la información de CubaNet en tu celular a través de WhatsApp. Envíanos un mensaje con la palabra “CUBA” al teléfono +1 (786) 316-2072, también puedes suscribirte a nuestro boletín electrónico dando click aquí.